Välbärgade, välekiperade damer i långa kjolar och tjusiga hattar i färd med att krossa fönster och kasta sten – så berättas gärna historien om den brittiska kampen för kvinnors rösträtt vid sekelskiftet 1900 när den omnämns på svenska. Slagord som ”deeds not words” – handling inte ord – från kampens storhetstid får bekräfta bilden av en rörelse som avstod från tal och debatt och istället satsade allt på handling.

Det är dock en begränsad, för att inte säga felaktig bild. Att tala och göra sig hörd – och särskilt då på platser där folk i kvinnokategorin inte ägde jämlikt tillträde som på gator och torg och i juridiska och politiska församlingar – utgjorde i realiteten en mycket viktig rörelsestrategi.

Ett exempel på en konkret och symbolisk talaktion som utmanade kvinnors underordning utspelade sig två år efter att den radikala rösträttsföreningen Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) bildats 1903. Under ett partipolitiskt möte i Manchester, där Winston Churchill och kommande utrikesministern Sir Edward Grey deltog, reste sig textilarbetaren sedan tio års ålder tillika första kvinnliga medlem i textilarbetarfacket Annie Kenney (1879-1953) och ställde frågan till männen på podiet; om de hade för avsikt att verka för att regeringen skulle införa rösträtt för kvinnor och mer specifikt kvinnliga arbetare?

Istället för att få svar på frågan blev Annie Kenney ignorerad därefter med våld nedtystad därpå utkastad och arresterad – och i valet mellan att bestraffas med böter eller sättas i fängelse valde hon det sistnämnda. Händelsen omskrevs i pressen av ögonvittnen som ett talande exempel på att kvinnor som sökte debatt blev behandlade som fredlösa och fråntogs sin röst.

Suffragetten Muriel Matters från Women’s Freedom League (WFL) åskådliggjorde villkoren ytterligare när hon 28 oktober 1908 tillsammans med ett antal andra medlemmar i WFL kedjade fast sig vid metallgallren på den så kallade kvinnoläktaren (Ladies’ Gallery) i det engelska underhuset (House of Commons). Med en högt och ljudligt uttalad protest mot kvinnors utestängning blev Muriel Matters första kvinna någonsin att tala i brittiska parlamentet (att sitta fast i gallret betraktades juridiskt-tekniskt som att ha intagit talarstolen).

Något förbud för folk i kvinnokategorin att studera juridik fanns inte, men eftersom kvinnor var förnekade juridisk personstatus (Solicitors Act 1834), blev de som juridikstuderande utestängda från att ta examen och försörja sig i (advokat)yrket. Därmed var de även portade från att skaffa sig de meriter som avkrävdes en politisk aktör i parlamentet då underhuset till större delen bestod av jurister.

Samtidigt ansågs den sorts rättsmål som i hög grad berörde kvinnokategorin, det vill säga sexuella övergrepps-, kvinno- och barnmisshandelsmål, opassande för kvinnor att bevista varför kvinnor sällan tilläts närvara i domstolarna vare sig som vittnen eller åhörare.

Att rättssalen valdes ut som en lämplig plats för feministisk talaktivism bör därför inte förvåna. Att bli ställd inför skranket gav både möjlighet att framföra kvinnorättsliga budskap till den laguppehållande makten, åhörarna och presskåren – och att direkt motbevisa påståenden om kvinnors ”naturliga opasslighet” i offentliga rum, en sorts argument som florerade bland kvinnorörelsens motståndare.

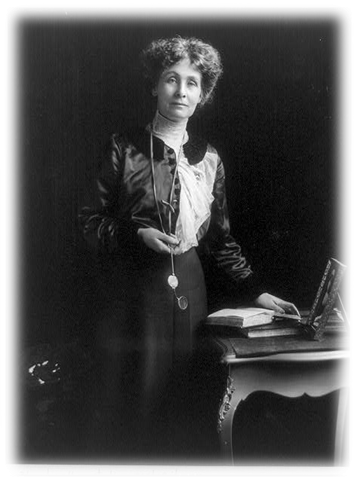

Suffragetternas mest omsusade talare, fattigvårdsinspektören och WSPU-ledaren Emmeline Pankhurst (1828-1928), erkändes allmänt som en ytterst skicklig talare, inte minst i rättssalen. År 1912 försvarade hon suffragetter som stod inför rätta anklagade för vandalism efter att regeringen Asquith brutit löftet om att införa en förlikningslag med avseende på kvinnlig rösträtt (Conciliation Bill). Några år tidigare, 1908, korsförhörde hennes äldsta dotter jur. kand. Christabel Pankhurst finansministern Lloyd George och inrikesministern Herbert Gladstone i ett rättsmål som gav stor uppmärksamhet åt rörelsen.

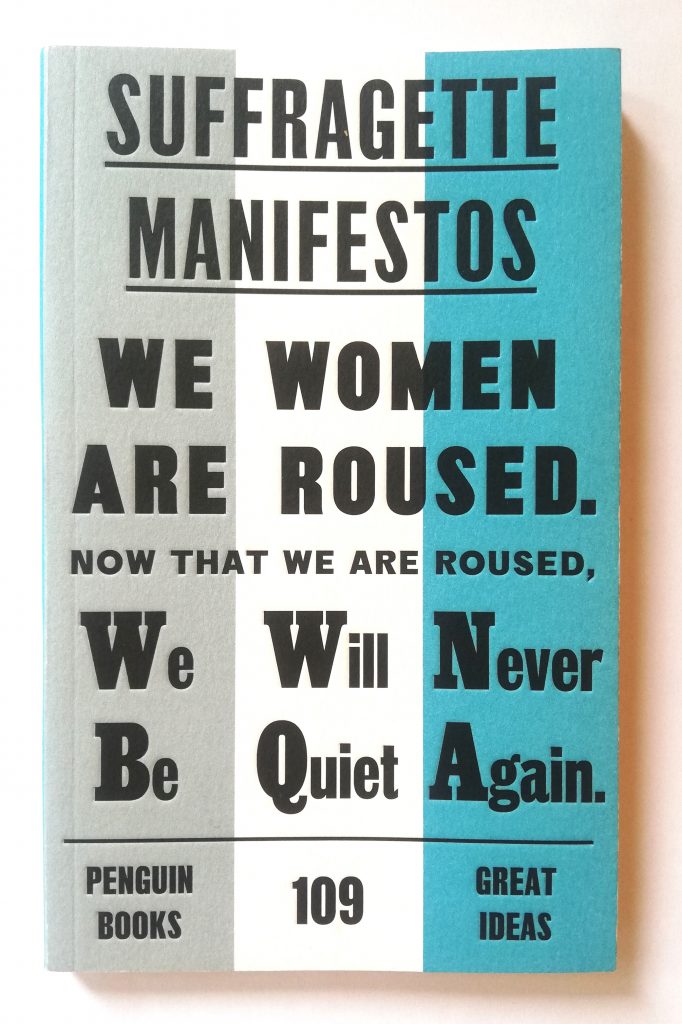

Emmeline Pankhursts på sin tid berömda tal “Freedom or Death” 13 november 1913 i Hatford, Connecticut, USA finns bevarat och utgavs häromåret i samlingen Suffragette manifestos (Penguin Random House, 2020). Här åberopar Emmeline Pankhurst kvinnors rätt till uppror som en del av folkets rätt att resa sig mot tyranni, men till skillnad från mäns blodiga strider, utan någon avsikt att äventyra motståndarens säkerhet. Den sittande regeringen har, påpekar Emmeline Pankhurst, att välja på att införa rösträtt eller åse rösträttskämparna hungerstrejka till döds i fängelset. Inspiration till kampstrategin att inte skada motpartens liv och lem hämtades från Chartiströrelsen som på 1830-talet använt sig av egendomssabotage i kampen för egendomslösa mäns rösträtt.

En annan i samtiden berömd utövare av aktivistisk talekonst – med något avvikande synsätt i förhållande till kampstrategier – var Louise ”Lizzy” Lind af Hageby (1878-1963), uppväxt i Jönköping och Stockholm och skolad på Cheltenham Ladies’ College i Gloucestershire, England. Redan 1903 talade hon offentligt som vittne i en rättegång i London med anledning av sin och kollegan och livskamraten/partnern Leisa Schartaus avslöjande reportagebok Eye-witnesses (omdöpt till Shambles of science) om plågsamma djurförsök i utbildningen på ett av Londons universitet.

Lind af Hagebys karriär som offentlig talare och debattör nådde sin höjdpunkt i april 1913 i en sexton dagar lång rättegång med anledning av den senaste kampanjen mot djurförsök. Domaren prisade Lind af Hagebys sätt att tala och föra sig som försvarare i rättssalen och flera av de stora tidningarna menade att Lind af Hagebys vältalighet utgjorde bevis för att kvinnor borde accepteras i advokatyrket och att det var hög tid att införa den kvinnliga rösträtten.

Året därpå, i februari 1914, när delar av rösträttsrörelsen börjat använda sig av konstattacker och sabotage av allmänna transporter och postförsändelser som medel för att få regeringen att lyssna, höll Lind af Hageby en serie föredrag i Queen’s Hall i centrala London på temat kvinnorörelsens problem. Lokalen var väl vald, 1913 blev Queen’s Halls symfoniorkester den första i världen att anställa musiker ur kvinnokategorin, och det var här Emmeline Pankhursts WSPU höll sina veckovisa möten.

Nå, vad hade den i pressen omskrivna talaren, antidjurförsökaren, feministen och WFL-medlemmen Lind af Hageby att framföra om rörelsens problem och möjligheter? Lind af Hageby inledde med att be publiken föreställa sig en rättssal där Kvinnan stämt Mannen för brottet att hålla Kvinnan i fångenskap medelst påtvingade barnafödslar. Föreställ er vittnena, uppmanade hon, se framför er alla de kvinnor som motståndarna till kvinnorörelsen inte talar om, de arbetande kvinnorna på verkstadsgolvet, de ensamförsörjande kvinnorna på gatorna, de prostituerade kvinnorna och barnen. Föreställ er vad de har att säga om sin situation!

Kvinnor omtalades och behandlades som om de alla var lika och hade allt gemensamt, ja, som om kvinnor inte ägde skiljaktigheter eller hyste sinsemellan avvikande åsikter. Och det fastän kategorin kvinnor var lika varierad som kategorin män. Att på enkelt vis fösa ihop människor under samma etikett var i sanning befängt och förminskande. Lind af Hageby förutspådde att tidens sociala rörelser, präglade som de var av ”femininitet” i betydelsen social uthållighet och ståndaktighet, framgångsrikt skulle komma att omvandla landets styre i riktning mot ”androgynitet, humanitarianism och feminism”.

Så var det frågan om kampmetoder – och här blev resonemanget med ens kontroversiellt och frågan retorisk: Kan upptrappade aktioner få regeringen att agera i rösträttsfrågan? Nej, löd svaret, inte enkelt så. Kvinnor hade självfallet lika stor rätt som män att använda diverse metoder, men när tredje part, det vill säga allmänheten, drabbades var det som om Jane i ett gräl med John klappade till Charlie; det vill säga det var inte en strategi att rekommendera om syftet var att omvandla det mansdominerade samhället.

Lind af Hagebys kritiska syn på aktioner som drabbade allmänheten var i överenstämmelse med Charlotte Despards Women’s Freedom League (WFL) och dess val av strategi. WFL har länge åsidosatts i förmedlingen av suffragettrörelsens historia – och det fastän föreningen dominerade i medlemsantal, blev den mest långlivade i rörelsen, verksam till 1961, och särskilt samlade rörelsens ensamförsörjare, arbetare och fritänkare, konstnärer, skådespelare, författare, vegetarianer, homosexuella och icke-binära.

WFL lyfte fram de kvinnliga arbetarnas situation, betonade vikten av att bilda lokala grupper och att bruka demokratiska processer. Föreningen arrangerade talturnéer, skattevägran, vägran att registrera sig i folkräkningen (1911) och spektakulära aktioner som Muriel Matters och andra aktivisters talaktion i underhuset 1908, liksom att året därpå segla över London i en luftballong med mottot ”Votes for women” – det sistnämnda en aktion som för övrigt kan ses gestaltas av Alec Guinness i en kort sekvens i crossdressande spelfilmen Sju hertigar (1949).

Lind af Hagebys diplomatiskt framförda klander av viss militans låg förvisso i linje med WFL:s strategi – men det stred samtidigt mot föreningens demokratiskt antagna policy om att inte kritisera andra suffragetters val (offentligt). Dock passade resonemanget väl till syftet att ge internationella perspektiv åt den brittiska kampen:

Rösträtten hade, framhöll Lind af Hageby, vunnit segrar i många länder och delstater, exempelvis i Kalifornien, Washington, Oregon och i Finland (1906) hade kvinnokategorin lyckats ta plats i politiken på samma villkor som manskategorin. Över hela världen hade tretton delstater och länder infört kvinnlig rösträtt och valbarhet till parlamentet – och än fler övervägde förslaget. Särskilt omnämnde Lind af Hageby kvinnors kamp för att nå inflytande och rättigheter i Kina och Iran.

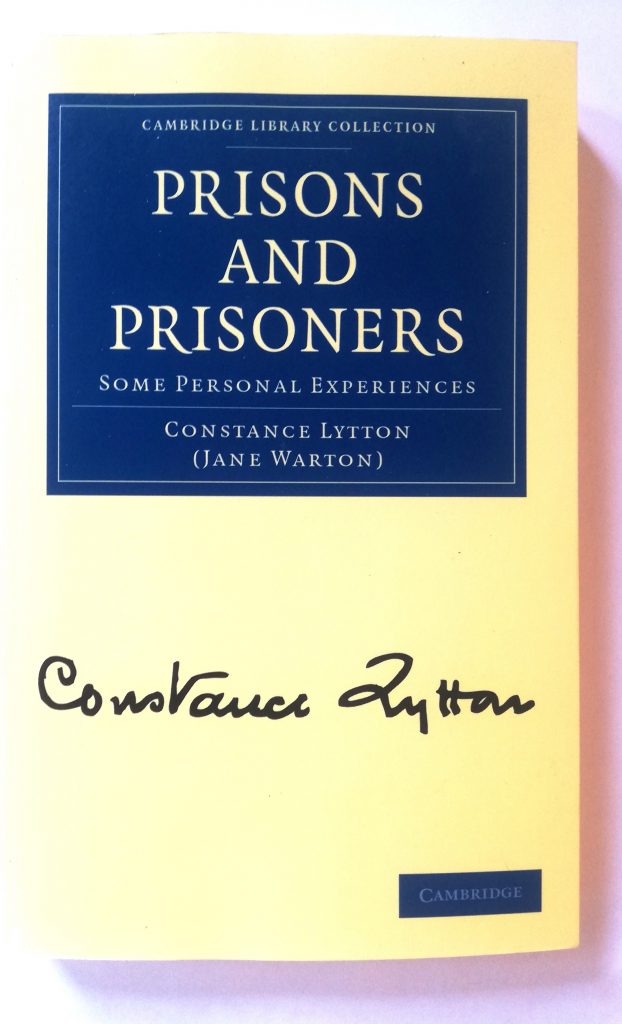

Någon vecka efter Lind af Hagebys föredragsserie i Queen’s Hall utkom suffragetten och vegetarianen Constance Lytton med självbiografin Prisons and prisoners, some experiences (1914). I boken beskriver Lytton (tillsammans med alter egot Jane Warton) kampens vardag; hur det brittiska parlamentet i över tjugo år samtyckt till kvinnlig rösträtt utan att göra något åt saken samt vad detta svek lett till.

Lizzy Lind af Hagebys och Emmeline Pankhursts respektive talekonst hyllades i tiden som övertygande argument för införandet av jämlika medborgerliga rättigheter. När första världskriget utbrutit på sommaren 1914 saktades kampen ned, och reformer för lika rösträtt, liksom rätten för kvinnor att verka i alla yrken inklusive advokatyrket, stadgades inte förrän 1918 (den begränsade rösträtten), 1919 (lagen mot könsdiskriminering) och 1928 (rösträtt för kvinnor över tjugoett år boende på öarna).

Lätt förglömt, såväl då som idag, är att tala är en akt i sig och att ord kontra handling i grunden är en skenbar, snarare än reell motsats. För eftervärlden kom suffragettparollen ”deeds not words” att skymma den stora roll talekonsten spelade i rörelsen. Som uppmaning till tidens brittiska maktägande manskategori att göra slag i saken, läs infria givna löften, passade den dock utmärkt.

Litteratur

- Suffragette manifestos / Barbara Bodichon, Frances Power Cobbe, Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline Pankhurst, Annie Kenney och tio andra, London: Penguin Random House, 2020

- Annie Kenney, Memories of a militant, London: Edward Arnold, 1924

- Constance Lytton & Jane Warton, Prisons and prisoners, some experiences, London: William Heinemann, mars 1914; omtryck New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010

- E. Sylvia Pankhurst, The suffragette, the history of the women’s militant suffrage movement 1905-1910, New York: Sturgis & Walton Company, 1911

Porträtt & forskning

- Emmeline Pankhurst, Chicago, 1913, foto Matzene, public domain

- L. Lind af Hageby, London, 1913, foto Lena Connell, National Archives of Sweden, i E L Gålmark, ‘Problems of the women’s movement’: Lind-af-Hageby’s assessment of the state of the British women’s movement in 1914 and the scale of the issues facing feminists, Women’s History Review, 32, nr 5, 699-722.

- Shambles of science : Lizzy Lind af Hageby & Leisa Schartau, anti-vivisektionister 1900-1913/14 / Elisabeth Gålmark. Stockholm : Historiska inst., Stockholms univ., 1996, tryckt 1997. ISBN 91-88786-24-2

10/9 2023

Läst ovan artikel? Swisha en summa till arbetet bakom: 123 698 03 95.

© Arimneste Anima Museum # 26