Anno 2009

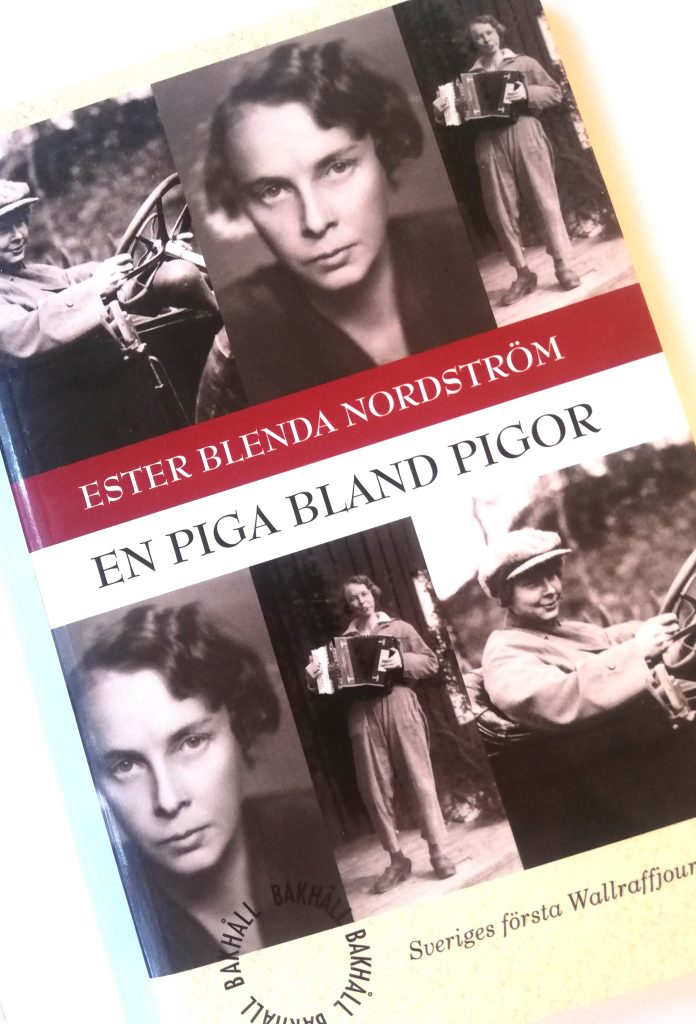

In the early twentieth century, the expression “the white whip” was both an image of the cow’s milk’s beam against the zinc bucket and a metaphor for the toiling of low-paid farm workers, i.e. the milkmaids, in Swedish called “mjölkdejor”. For those endowed with perception for other creatures, it reflected the situation of cows in Swedish agriculture as well. Ester Blenda Nordström, early undercover journalist and suffragette, showed such perception when she, in 1914, depicted both the everyday life of the milkmaids and the calves’ protracted crying for the cow and the milk, in her book En piga bland pigor [A maid among maids].

However, in Nordström’s time, the agricultural industry was only in its infancy as cow’s milk for sale became a novelty for the general public at the end of the nineteenth century. Animal husbandry was turned into mechanized business and “the white gold” extracted from the cows’ udders was launched commercially as a natural feature of Western food culture. Colossal bosoms are today carried by cows who are forced onto what is called a “rape rack” where they are inseminated to constantly be pregnant and give birth to an offspring that is taken from them. Simultaneously, their udders are kept in the gorged state in a circle that does not end until the cows’ bodies cannot be exploited any longer. As in Nordström’s time, the offspring is transformed into a so-called by-product soon to be separated from the cow. In most cases, this implies that the calf is saved in a cage for a few weeks only to be transported and killed at a slaughterhouse without ever having socialized with an adult from their own species or even experienced nature.

How many people take up the fight against today’s false advertising of cow milk production and testify like Nordström about the plight of calves and cows? In societies endeavoring for the modern, old habits, customs and products must of course be subjected to scrutiny. Is cow’s milk a product to invest in? Is it modern; is it suitable for the present, and for the future? Or ought it perhaps rather belong to history; a northern European cultural remnant to replace in the face of pressing conditions such as environmental degradation and climate threats? Cows are today bred in such large numbers that their combined physiognomy contributes to almost forty percent of global anthropogenic emissions of the greenhouse gases methane and sixty five percent of nitrous oxide, gases that are twenty up to two hundred times more harmful than carbon dioxide, respectively. According to a report from FAO, overgrazing and forage cultivation for meat and cow’s milk production is a major factor behind today’s erosion and deforestation, as well as the decline in biodiversity.

The norm of the white northern Europeans’ milk as the only existing milk has given the industry an EU patent for the word; and this although the world is full of milk variations: coconut milk from Southeast Asia, almond milk from Southern Europe, soy milk from East Asia, pea milk and oat milk from fields in the North. In China, there is a traditional diet without cow’s milk and with small amounts of animal products, yet China has been convinced to import Western diets and with them the dairy industry. When China, last summer, was hit by the milk scandal in which small children were injured and died from cow’s milk products which had been added with melamine, there was silence in the media about the fact that over eighty percent of the country’s population are intolerant to cow’s milk.

In fact, cow’s milk is ill-suited as a global food: an equal proportion, up to eighty percent, of the world’s human population does not tolerate milk, is either lactose intolerant or allergic to cow’s milk protein. The northern European milk variety, which has received such large investments and government subsidies during the twentieth century, is thus hardly an appropriate export product.

Still, the Swedish Minister of Agriculture recently voted in support of the EU’s export subsidies of cow’s milk and butter made from cow’s milk. Sweden’s vote implies that the cow’s milk industry can produce surpluses on the market and thus push down the price of similar products from countries outside the EU, so-called dumping, which leads to worse conditions for food production in poor countries, a production which, as it happens, is carried out by a large majority of women. If justice were of interest, the Swedish Minister of Agriculture would instead strive for the removal of punitive tariffs and trade barriers. In this way, the EU would be able to buy other types of milk at a fairer price and consumers in the bargain would get more to choose from.

Such a policy would provide opportunities to think in new and postmodern ways: Why must ‘milk’ be just one single kind of milk? For example, oat milk does not pose a risk of zoonoses (animal diseases transmissible to humans) that can turn into epidemics and pandemics, diseases which, according to the Swedish Defence Committee, constitute one of the three biggest threats to security right now. It significantly reduces the risk of allergies, creates little or no environmental damage in the Baltic Sea and other seas and lakes, saves energy and land and fresh water, does not imply animal cruelty and, it does not pretend to be the only indispensable milk. Ester Blenda Nordström would have applauded an animal husbandry where cows and calves are allowed to live and work only for a bit and in small numbers. She understood, to paraphrase the Swedish poet Sonja Åkesson, what it meant to be used as white man’s milk.

A more varied and fair milk market would make it possible to finally put down the white whip. The whip that “doesn’t tickle their fat necks” (“The State and the capital”, Blå tåget, 1972) but the world’s industrialized cows next to all the low-paid or unpaid women who produce most of the world’s food. When in our time there exist different types of milk, it is remarkable that both state and capital chooses to keep the cow’s milk industry going.

Previously published in Swedish in Arbetaren 18 March 2009

© Arimneste Anima Museum # 29-30