Meret Oppenheim’s Ma Gouvernante

Anno 2005

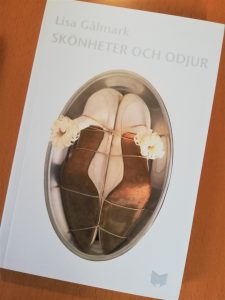

On a large silver plate of stainless steel resides a pair of white pumps. The dark sole is turned, and the heels are decorated with white garnish paper. A cotton string ties the served object into a rectangular check pattern.

When Meret Oppenheim’s artwork Ma Gouvernante, My Nurse, was exhibited in Paris 1936, a visitor approached the work and smashed it up (a replica was created for the retrospective exhibition at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1967).

The smashing up of exhibited art works forms a proud and fuming tradition of spontaneous art attacks. In the 1980s, for instance, a painting by Lena Cronqvist, exposing the opposite of sibling idyll; the older child is attempting to drown the younger, triggered a spectator in the audience to smash her handbag into the artwork.

But what afflicted the spectator in Paris? What where her thoughts when she decided to attack a pair of high heels on a deep dish? I will here depict what I call the anthro-androcentric logic; the elite human male as the norm in relation to the category of animals, and consequently, to woman, worker, stranger; and I will suggest, that what appeared irrational, i.e. to approach the symbolic art work to smash it up, instead may have been a rational reaction to that very logic.

In Western history, rationality has been interpreted as deliberation and decision, in contrast to the body and the bodily which were rather perceived as the opposite: work; manual work which the animal, the woman, the slave, the prisoner were commanded to effect with their bodies. Those who possessed opportunities to use their rationality decided that the others must use their bodies so that the possessors may plan how manual work, in general, and in the future, may continue to be carried out by the others (and not by the possessors themselves). Thus, the others’ rationality was left out, or seldom used. And, so it was, that working women and men, slaves, wives, servants, farmhands, maids, children, and the working animals beside the working people in mines, sweatshops, mills, in front of carriages, and ploughs became dispossessed of their self-governing rationality.

In world history, because of the European colonization of other continents, the ruler has most often been a man who is white skinned. However, all governing power has not been possessed by white men but enough power has been possessed by white men to give the world a deeply entrenched set of values: ‘white man’ is the human with the highest status because this category is in majority where there is power or chance of attaining power.

However, a ‘white’ ’man’ must not be perceived to be having a whitish skin; among powerful white men there is space for some non-whitish, and for some individuals of organ equipment other than penis equipment. Granted that these wrongly equipped make up a minority, and granted that they employ their rationality so that the rightly equipped remain in power, they will fit in and become nearly the same as ‘white’ and ‘man’.

However, all white men are not ‘a white man’. A ‘white man’ must be a rather mighty, and wealthy, non-worker: ‘No white men work there’, it was said of the lumber industry on the North American west coast at the turn of the 20th century, ’only Swedes do’.

The kind of rationality which suggests that white human masculinity implies the highest value stands in contrast to the notion of the bodily. However, it also stands in contrast to compassionate emotionality. When compassion is connected to work and body, it has generally been handed over to the others: In a white anthro-androcentric culture compassion towards people in power has a conserving function, while compassion felt by people in power must be pushed away since it entails the risk of lost and or shared power.

Rationality of power stands in contrast to the body, to labour and emotion, but only as a controlling tool for the superordinate. To the rulers themselves, bodily expressions, sexuality for example, are highly valued rights which powerful rationalities may satisfy by commanding the empathizing labouring bodies: the wife’s and the prostitute’s invisible domestic or public sex work, or the raping of their bodies.

European subduction of the other, the power of the master over the women, and the children, and the servants at home, and the workers in the factory; the power of the land lord; the big hunt, and the everyday slaughtering of animals, was often motivated and formulated as the conquering of ‘primitive’, ‘virgin’, cultures. Subduction of nature and the ‘wild’ was depicted as the same as wilderness seeking its tamer and coercer. The superordinate’s sexualized conquering project, this material and immaterial piece of art, was launched as the ‘spreading of civilization’.

The dualism of rationality and body, and the corresponding practice, decision-making versus work, ought not apply to subordinated bourgeois women in Northern Europe at the end of the 18th century. Hard every day manual labour was not their trademark. But as the literary scholar Anne McClintock contends, the life of leisure was only these women’s character role. Notwithstanding the homes of the very few extremely wealthy women, most of the households did not keep several servants.

Behind the velvet curtains, alone or beside the maid, the wife laboured. In contrast to the work of the maid, the wife’s work was not to be seen, and not to be valued in money. She must be a fetish, a provided for doll with untarnished hands. The art of the bourgeois wife was a multitask; working hard and at the same time presenting the toil as if it had never taken place. ’Dinner is served’ equalled ready roasted birds on a deep dish from nowhere.

Now, let us return to the site of the spectator attack in Paris 1936. What caused the lady to approach and attack the artwork?

Perhaps the surrealist Oppenheim deployment of the shoe metaphor sent a message from the subconscious. The barbecue string tied around the shoes on the deep dish was a metaphorical representation of the square order, the ruling rationality itself. The high heels were the cultural sign for ‘woman’, giving witness to the experience, and the observation, of being the trivially enforced decorated object.

The culturally sanctioned sign for ‘animals’, perceived both as a symbol, and as a real threat; other subordinated groups are always at risk of being transformed into aesthetically appealing parts.

The master technique of the anthro-androcentric rationality is to make complicit; to make the subordinated fit into the order. The subordinated are commanded to work, and kill; the subordinated are commanded to cook and serve. The subordinated are ordained to make the order their own, and to relish it.

The object, the shoes in Oppenheim’s artwork, is painted in white and brown colours and is given ornamentation; the alluring beautifully formed ritual tells you what will happen should you not obey. What remains is to partake in the meal, the consumption of the impossible-to-recognize seasoned dead body, the palate’s bribe for the project of submission, here as cuisine.

’Every new idea is, naturally, the same as aggression. And aggression is a trait that is directly opposed to the image of the feminine, which is carried within by the male and projected on the woman” Meret Oppenheim said in her speech ’Woman and Art’ from 1975.

The spectator sees herself serve, and be served. She encounters a symbol of a rationality deprecating her own and others’ rationality, her own and others’ bodies; a symbol of a rationality without compassion which bisects sex, ties up sexuality, and transforms some bodies into the everyday served object. And, she sees work done by somebody like herself, but, who, unlike herself, has been assigned a value, and has been paid (though poorly).

The one who eats this, is eaten, eats herself. And now she gets the rational idea of getting rid of it all.

Or, she just got hungry – for something else. She takes that which she has.

‘With berries you are nourished

In shoes you are consumed

Husch, husch!

And the most beautiful vowel is emptied’

Meret Oppenheim

from her poem: ”Husch, husch, der Schönste Vokal enleert sich”, 1934

Previously published in Swedish in Bang magazine, no 3, 9 August 2005

Photo: Book cover Skönheter och odjur, Makadam (2005)

© Arimneste Anima Museum #10